How do I find

some one that may have seen any of this?

A particular event occurred

during the Iwo Jima invasion that this veteran is seeking

answers for. Below is a short story of Bill Newbauer's

experience during D-Day+1 (20 February 1945) that took

place. He is seeking answers. He is attempting to reach out

to someone who was there and witnessed what happened below.

If you can assist in his search, please contact this web

master.

One old

sailor needs help, witnesses!

"I was on the U.S.S.

President Jackson (APA-18), an engineer on a L.C.V.P., at

Iwo (Jima). This small boat landed a fire control Jeep and a

couple Marines at what was "Red Beach" at one time. This

Jeep was upset in our boat, we came through it all right, I

only lost my small machine gun in the drink. It was loaded

once more, very rough seas, and we headed to and down the

beach until called in. No beach party, this was on the 20th

(of February), we held in position with the screws and

rudder. The jeep got off, don't know how far--- we broached

and the screw picked up a floating line, all power gone!

Some how I and the two others made it to shore. I don't

recall any names at all, I know it happened, I can't find

any witnesses, I was behind the bowdoors of a craft, I think

a L.S.M., until the next afternoon when I got a tow back to

the Jackson. I had one shark knife and I was scared, I saw a

lot of the stuff on the beach, now like a nightmare. How do

I find some one that may have seen any of this?"

Webmaster's note: A few days

ago, after spending the last month or so playing catch-up

with regards to the three web sites that I manage, due to a

crash of my external hard drive containing five years of

research materials pertaining to this web site as well as

two Civil War web sites, I came across an entry in the World

War II Guest Book. This Guest Book entry led to the

following follow-up story as dictated by Bill Newbauer to

his son Steven. The following story is very interesting and

moving reading. I highly recommend it!

Many THANKS Bill and Steven

Newbauer!

In His Own

Words

The following is a

composition my dad made up a few years ago which he

titled...

"It's about my little part in the big

war":

The following isn't meant to

be a "Blood and Guts" type of story, there was some

witnessed in close proximity, some of this will be mentioned

as I try to recall the names and places I was a witness to.

I got into the Navy by being a "Selective Volunteer", not

too many of us around, I wasn't drafted, in fact, the draft

board didn't know if I would be called or not. They even

made a phone call to the Selective Service Headquarters to

try to find out but they had no definite answer. I had a few

deferments because of my job and being married, with one

child and my age bracket wasn't being drafted at that time.

I was told that if I volunteer I could pick the Navy, be in

for the duration plus, I found out later what the plus was

and that I would not have been drafted, too late! I turned

down my latest deferment, got my severance pay and did the

volunteer thing. A physical in Auburn, Indiana and soon I

was on my way to Indianapolis to be sworn in plus a lot more

physicals, tests and soon I was on my way to Great Lakes

Naval Training Center near North Chicago. I began a new life

which I had problems adjusting to, at least for a few weeks.

This is something you wouln't wish on your worst enemy (if

you had one). I was in a six weeks company, kept very busy

all of this time. I was glad of that. We stripped down to

just a smile or a sneer, whichever, put all of our

belongings in a cardboard pre-addressed box, ran around bare

for half a day, finally got some Navy clothes. I broke my

glasses putting on a 'blouse'. I didn't wear any glasses the

rest of the time I was in the Navy. I soon learned what

really being insignificant was, what hate and mistrust was.

These people dealt it all out. We drilled, marched, had

calesthenics until some of the guys couldn't do any more. I

made out somehow. I wasn't the best athlete at that time in

my life. We swam a lot. I liked to swim and dive. We jumped

from towers into the water to simulate getting off of a ship

in an emergency situation. We learned to use clothing for

life preservers (entrapping air in them) and swam the length

of the pool underwater. This was training for the event of

having to escape an area of burning oil or fuel floating

atop the water. Each day was filled with the above plus

classes, watches to stand in the area buildings, and good

ol' KP duty. This was a long day. We had to get up in the

night, dress and drill for hours, another sort of punishment

when someone had made a mistake and we all paid for it. With

all the hatred I had I began to shape up. I almost enjoyed

it!

These punishments went on all

day too. If a man did something and really messed up, he was

forced to drill with full gear, rifle and sometimes with his

hat in his mouth if he had talked to get the punishment in

the first place. This drilling went on for hours, usually

the guy would collapse, you didn't help him as if you did

you would take his place! I saw two men die from this sort

of punishment. It does weed out the unfit and the weak! The

six weeks finally rolled by and we were no longer "boots".

We were given a few days leave during which time I went

home, of course. The time went so fast. I was soon back at

Great Lakes and was selected to go to Basic Engineering

School. This lasted about a month. I didn't really learn

much. It was like a refresher course of what I learned at

the specialist school in Fort Wayne. This school was put in

my records which helped later as I was assigned to groups

with similar backgrounds. I ended up with a nice bunch of

guys which was a welcome change. This group was supposed to

go to a diesel and gasoline engine school on the East coast,

but a storm took down a lot of the buildings so the plans

were changed and we were sent to Camp Shoemaker, California,

up in the mountains. This ended up as a place to stay until

more changes were made in our orders. The guys were broken

up once more. We had more serious calesthenics, rough

workouts, hikes, and anything to keep us in shape. It was

very cold at night and hot in the daytime. We were all

rounded up, put in a stockade and locked in. This was with

all of our gear so I figured this was some sort of final

move. At night we were loaded on a Navy bus. It was not the

large group I started out with, probably only about a dozen

of the bunch that I got to know a little. We were taken to a

pier in Oakland, mustered in and marched around to the far

side. There she was ... my first ship, the President

Jackson, all camouflaged, loaded with landing craft and she

had lots of guns all over. As this was my new home I went up

the gangway, saluted as I should and was escorted to a

partial deck above the forward end of the mess hall. This

would be my "room" for a week or so, living out of my sea

bag once more. Finally I was assigned a rack in the aft end

of the ship and a locker about 40 feet away., but at least

the "head" (toilet) was very near by. I was right by the

hatch opening into it. There was no welcoming committee on

this ship, only an order to follow a first class machinist

mate below to the boiler room.

|

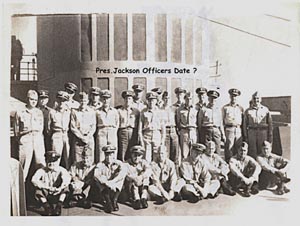

Officers of the

USS President Jackson

Click on Image for Larger View

|

This is quite an experience.

Very soon I was told that this was where I would be assigned

as a watertender, striker, to advance to a Machinist's Mate

Third Class Petty Officer. I stood a trial watch and was

shown my jobs to do. These people were not really the best

of teachers. At this time the ship needed only one of her

boilers in operation and only three burners in use. I caught

on to the job rapidly and also the routine of living each

day, touring the ship on my own. So far so good. The first

task I had was as the ship was moved from the dock at

Oakland to one at Hunters Point, farther south, to have some

work done on some steam lines and newer radar screens added

topside. My job was to run up two decks to see how far we

were from the pier so that we would know when to shut down

unnecessary burners. My judgement must have been good, after

a few fast trips topside we made it alongside the dock and

tied up without popping any safety valves or losing any

flame in the firebox. We left the States with a sister ship,

the President Adams, with a blimp for an escort to watch for

subs. We zigzagged towards Hawaii, picking up a couple LSMs

for escorts fo the trip. Not much happened at this spot. We

anchored in Pearl Harbor. I was off the ship one day during

which I took a trip to downtown Honolulu, mostly just

looking around. The place was full of servicemen. Most of

them were drunk and loud. We tied up at a pier next to a

Russian freighter which had big buxom women sailors on deck

doing the usual work topside. The Jackson and the Adams left

Pearl Harbor with two smaller landing type craft for escort.

They were out of sight in the swells most of the time. We

headed for Noumea, New Caledonia east of Australia. Enroute

we crossed the International Date Line and the Equator at

about the same time which meant the usual initiation which

lasted a couple of days longer than normal. Nothing about

this can be considered normal and this crew pushed the

capers to the limit. The captain finally put a stop to the

proceedings and we got back to the normal routine. Each day

the work was done, the watches were "stood" and the meals

were served. And we had General Quarters day and night and

all hands had to man their assigned battle stations when not

actually on watch. The guns were manned and very little

sleep was had. We anchored out from the shore at

Noumea.

The ship's boats were put to

use doing all sorts of delivering and hauling troops to be

put aboard the Jackson and the Adams. These men seemed to be

all rated and an elite bunch, mostly tehnicians, probably

engineers and gunnery people. I never did find out, but our

job was to put them on New Guinea which we did. We also

unloaded supplies, ammunition and a few trucks to haul them

inland. We stood by for a day then headed in a northerly

direction on up to Guam which was taken at that time

although it was still under some battle conditions in the

jungles to the west. We had another journey to make, we

loaded up a few hundred troops and went farther east to

Guadelcanal. This was to refuel and take on supplies. We

spent one Christmas tied up there. Soon we headed back west

and farther north to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines where one

of the larger landings in the Pacific was in progress. We

stood by and made smoke to shield ships in the area. The

naval battle was north of us but the Jap planes were out in

force with day and night bombings and suicide planes all

around. The gulf was full of anti-aircraft projectiles,

tracers and explosions up in the sky where the planes were

coming in from the land. My General Quarters station was as

the "talker" on one of the gun mounts. The battle conditions

improved in a couple of days and we pulled out to go west

through channels, some of them so shallow we had to take

soundings from small boats to get through safely. Finally we

made it to the China Sea and headed north once more past

Manila and Corregidor where the battle was still being

fought. Our mission was to get the troops we had aboard

father north to Lingayen Gulf in Luzon. We entered the Gulf

and anchored at the south end of a large bay. The troops

were put ashore, mostly up rivers and to small villages

which we had taken back from the Japs a few days before. Air

attacks continued daily with lots of suicide planes. One

suicide plane took out two LST landing crafts tied up

alongside each other located about a thousand feet from us.

They both were heavily damaged. Big guns in the mountains

kept firing at the bay. We seemed to be lucky as usual as we

had no close hits. You could see those projectiles coming

through the air which was a very scary sight. There was

great relief when we watched them fall short or go over us.

None of them seemed to do much damage. Our planes seemed to

be very lucky too as they flew through thousands of bursting

projectiles in the low sky. We had these air raids daily

while in the bay. While all of this wierd sort of battle was

in progress the routine aboard ship went on as it did each

day.

Whether underway or at

anchorage General Quarters was all day and night. Our

regular watches usually were top priority. The gun crew

could usually be a man short unless we were actually firing.

While serving in the boiler room I developed a bad rash all

over my body. The people in Sick Bay could not do much with

it so I was ordered topside to get some sunshine. This is

how I got into small boats. I had other duties as well like

working in the mess hall part time. I had been made head

mess cook for a week or so and my job was to make sure all

of the cooks helpers were in the mess hall on time. I had to

learn where all of them were quartered and get them up to go

to work on time. The rash I had finally went away but I

stayed topside and assigned to small boats the remainder of

the time I served aboard the Jackson. We left Lingayen Gulf

and headed back south in the China Sea. Each morning more

ships would be in the convoy and now totalled a dozen or so.

The Zeilen was alongside us about 300 yards to our

starboard. This was another period when we were at General

Quarters day and night as enemy subs and planes were all

around us. We dropped "ash cans" from the stern until they

were all gone. A Tojo, Japanese twin engine fighter bomber,

came overhead. We were ordered to hold our fire. A turret on

the Zeilen opened up firing and the tracers which were like

a ribbon going out from the ship were used by the plane to

lead it right to the ship. The gun turret was fired upon and

all of the crew was hit or blown over the side. The plane

went two decks down exploding all the way. Twelve men were

killed or lost. The ship slowed to a stop to get organized.

The whole convoy slowed to about ten knots until the raid

was over but kept moving south. The next day the dead were

buried at sea. Then we proceeded at 15 knots to the southern

part of the Philippines again. The convoy broke up and the

Jackson went east to Guam once more. In about a week we

loaded up a few hundred troops, trucks and armored vehicles.

It looked like another landing coming up for sure. At Tinian

we took on fuel then went in a northerly direction. In a day

or so the engineers and boat crews were called to assemble

on the starboard promenade deck. Some officers were handing

out information concerning where we were bound. They had a

topographical map of an island shaped like a

pear.

It was a volcanic peak

jutting up through the ocean. The main flow went northeast

to form the wide portion of the island about three miles

across and five miles long. The volcano was at the extreme

southeast end. The only beach was what was eroded from

constant wave and swell action ... no more than fifty feet

inland. This we found out later to be black ashes, firmness

similar to quicksand. Of course, the map didn't point any of

this out. It was Iwo Jima. I had never heard of it before,

but soon we learned a lot about it. The navy had been

shelling it for a couple of months with no damage at all.

Planes had bombed it for the same length of time, yet still

there was no damage. The island was honeycombed from one end

to the other. Suribachi, the volcano, was one huge fortress

with tunnels and gun positions at every level, and it was

tall. This was probably what we were trained for, the

roughest of all of our landings. We had a few days before it

was to happen. I don't recall any special training which

took place at this time ... only getting the boats in top

shape, tanks full of fuel, batteries charged and a couple of

extra boats added to our usual complement. All of the

cables, ropes and life jackets were placed aboard. We all

did a lot of staring at each other. At this time I still did

not know the names of any of these people nor did anybody

offer to be the least bit friendly. On the day before the

landing we were barely moving north towards Iwo when I

looked over the port side and saw a body floating in our bow

wake. It was headless ... probably one of our pilots. This

was not too unusual except that I had dreamed of seeing the

same picture the night before! The Jackson pulled up within

about a quarter mile, too close as we found out soon. We

were hit with small fire, some phosper 40 mm shot. This

spatters like solder. A few guys were hit. The 'take cover'

order was given too late. Needless to say, we moved out

beyond the range of those guns. The landing took place in

daylight, unusual for us. The boats that were needed were

launched. The boat I was engineer on was one of the first.

We circled a short distance from the ship until called in.

This sea was the roughest I'd ever been in with swells at

least 15 feet and close together making a troop loading very

hazardous. Boats all around us were attempting to take on

troops and other cargo. I am telling about the one I was

on.

Some of the happenings are

vague to me now. Our load was a Jeep type vehicle loaded

with radio equipment to direct fire from the ships farther

out. There were many cruisers, destroyers, rocket ships,

escorts and about any type of war ship the navy had. This

gunfire from these ships was going on all around us with no

let up all day and night long. Two cruisers within a quarter

mile of us fired broadsides all day and most of the night.

This helped us keep our heads clear and down! We were called

in to load up and made a nice approach and tried to hold

against the ship ... sometimes against the rail ...

sometimes under the belly below the water line. The navy way

at this time to lower any piece of equipment was to fasten

it to a cable which goes up to a pulley, down the boom to

another pulley, across to a winch in the center of the deck.

Other winches moved the boom from side to side, in this

case, over the side. Another winch lifted the boom to the

height needed. This isn't all of the niceties. A man stands

at the rail looking down at us, wondering why we can't hold

the boat any closer and in one spot. He signals to a man who

handles the winch controls who raises or lowers the vehicle

hopefully gently and accurately into our boat. The first

attempt was a disaster. The Jeep lit on the gunwale on my

side, sent my machine gun to the bottom of the sea, and

upset in the boat. Luckily there was some slack in the cable

and we got it lashed up so it could be hoisted and relashed

to try once more. The war continues around us, we try to

hold our position as well as possible. As a swell took us up

very high the Jeep was on its way down again, and as we

dropped back down the Jeep was lowered perfectly into the

boat. We unhooked all cables and lines so they could be

taken back up and then moved out to circle until called in.

The cox'sn, now at the wheel, somhow started in at the wrong

place. There was a huge rock on shore. No problem there

except a few Japs who owned that rock decided to protect it

and opened up on us with rifle fire. We moved out of there

very quickly. Once more, down the beach at the foot of

Suribachi we found our spot to land the Jeep and three

Marines, all radiomen, all with tears streaming down their

faces. I think I know why. We were getting a lot of very

close hits. I am so glad they were only close. The water

spouts would be several feet high.

We were signalled in and

headed to the beach, what beach there was. We were at full

speed. I lowered the bow ramp. The crank used in lowering

the ramp slipped out of my hand and put a nasty gash in my

arm, through a denim jacket and shirt. We held the boat in

by turning the rudder and holding the power on. Then it

happened ... the propeller picked up a line floating along

the beach. It had a length of cable tied to it, within a

couple seconds the reverse gear was literally burned up and

we had no power at all. These high swells continued in to

shore, although now a little smaller but still very strong

with a rip tide effect. We immediately broached, the

starboard side was crushed in and we were pulled out about a

hundred feet, to be tossed about. We scrambled over the

lowered ramp and made it to shore. It was not the fanciest

swimming done but it was effective. I got around the bow of

a landing craft. I think it was an LCI, beached to take on

casualities. This was a fairly safe place as long as there

wasn't a big mortar projectile heading my way. I didn't have

a weapon, only my knife, so I just stayed there until the

next day. This was the real thing, with a lot of those

mortars dumping their shells in the nearby area. I saw a lot

of guys get it. My luck still held out. I didn't run out in

the open and ask for it. I wanted to come home if possible.

All day and through the night until about noon the next day

I witnessed up close what the landing was really like on the

beach. I had a taste of it in the water. I did a lot of

peeking around the bow of the boat but I was taking cover

from whatever came my direction. I can see why we had eight

or nine thousand casualties the first day, not making it to

the first ridge above the beach. Around noon the next day a

landing craft, an LCM, a bit larger than the one I was on,

landed some equipment and offered to tow our boat out to the

Jackson. We accepted, located our boat about a hundred yards

east of us, still afloat but beat up. We lashed the two

boats together and headed out. I had to ride in the wreck.

The swells were still twelve feet high near the island. The

lines broke twice on the way. As we neared the Jackson,

Larry Pabst, a friend and a carpenter, was at the rail. He

looked down and yelled, "There's old Bill! We heard you were

dead." I don't remember how I got topside or how the boat

was hoisted. I know I went to my rack, crawled in, helmet

and all, and soon I was out, dead to the world.

In the early evening our

Master-at Arms awakened me and said I'd better go to the

mess hall to get some food. I had only eaten a couple of

candy bars in all the time I was off the ship. After the

food and a shower I felt better. I had gained a few friends

I hadn't known before. I reported to the first class

machinist's mate. He found out I was assigned to another

LCVP like the previous one I had been on. The duty was to

'be in the water' to do any job that needed done, on call.

The unloading was still going on. Troops were coming over

the side to board the landing boats, now in smaller numbers.

Among them were gunnery teams and some BAR men. The BAR was

a larger than usual machine gun which was very heavy. One

man lugs it around while another man carries the ammo for

it. The seas were still high so landing operations were

still scary and risky. A BAR man was coming down the net

when he lost his grip and fell into the sea ... going down

below the curvature of the hull and up to to where he had

lost his hold. The gun was still on his back and shoulders.

The Chaplain of the Jackson, who was very overweight,

crawled down the net far enough to get the soldier's head

between his upper legs, but he couldn't do anything more

except half drown the man who was now about unconscious, so

he let him go back into the water. At this point our boat

attempted to rescue the soldier. I lowered the ramp about to

the water line and we attempted to get closer. We were

moving up and down some twelve feet or more. I tried to get

into a position to try to grab the soldier, but there was no

way. It was just too risky. The "feel" of the ship pulled

our boat in too close. I was lying partly on the gunwhale

and when the boat moved toward the ship my body was as a

"fender", but I am not that tough so I got two broken ribs

out of this. We maneuvered back out away from the ship and

another boat approached but not as close and a young crew

member jumped in with a life jacket on and some lines

(ropes) to be used to pull him and the soldier back to their

boat. I don't think that soldier had to go in with the

landing that day. I will tell more about the young crew

member who jumped in to rescue this man later. Later I was

allowed to climb up the largest cargo net to have about a

mile and a half of tape put around my ribcage. The pain was

not all that bad yet. I had to go back aboard the small

boats and continue my job there. We were assigned to a job

along the beach, pulling out and sinking the disabled craft

that cluttered up the shoreline. Probably there were some of

the crew and soldiers still inside these crafts. We didn't

check.

At the end of the first day

of this new assignment to this landing craft we contacted

the people on the bridge to see if we could be hoisted. No

way, it was too risky, swells too high. We were handed down

some food in containers that kept it warm. A refueling hose

was lowered down and we filled the tank. We shoved off and

continued our work. There was no relief from the high seas

and no hoisting. More food and fuel was passed down to us.

On the fifth night we were finally caught up with the

salvage jobs and went out to the ship but were denied

boarding again. We had it with this task! A person can only

take so much. We were exhausted and just didn't feel like we

could possibly go on. We pulled alongside the ship and tied

up to a cable we called the sea painter which ran the length

of the port side. The two men with me crawled up the cargo

net and were supposed to try to get somebody to relieve us.

I had to remain in the boat until that happened. As I waited

the line tying the boat to the cable slipped along the cable

and the boat had moved back over half way along the ship,

just below the promenade deck. I had given up on any hope of

being relieved as the two men of our boat's crew never

showed back up nor did anyone else. My intentions were now

to get aboard somehow. There was no cargo net back here but

there was a fender just below the top deck made up of a

metal drum covered with rope netting to make it softer and

flexible. It was hung on two lines, one on each end. It

looked as though the lines might be within reach when the

boat was at the top of the swell. I had to stand on the

stern sheet, no rails at all, and reach up to grab the line

on the end of the fender. Of course, after grabbng the line

I was hanging in mid air as the boat dropped down in the

swell. I was pretty scared.

I was never too good at

climbing up a rope but I decided to improve that night.

Somehow I made it to the rail and got over it to lay on the

deck and try to remember what ship I am on. A guy in a

hammock saw all of this, and later he told me that he

thought I would make it so he didn't come to help me. I made

it down to the Master-at-Arms compartment, awakened him and

told him what had been going on. The two guys from the boat

hadn't told anyone anything. They found a rack in a troop

compartment and "passed out". I could have been in serious

trouble with some officers, but the Master-at-Arms was a

nice guy and said he would handle everything. I went to sick

bay, got checked out, and was given a small bottle of

brandy. I headed for my rack. I took a sip of the brandy but

it was not for me! I went over to the far side of the ship

to where one of my shipmates was asleep. I knew he loved

anything with alcohol in it. I held the small bottle of

brandy under his nose. He woke up and drank it down quickly.

We talked a little before I went to sleep.

The Master-at-Arms awakened

me to get some food and so could get a hot shower with fresh

water while it was available. No one was the least bit

interested in what I had been doing so I didn't tell anyone

where I had been for the last few day before this. I was

assigned a watch on the gun deck which was the highest deck,

but below the bridge, abaft the stack, like from 90 degrees

to 270 degrees to watch for anything that moved or was

worthy of reporting to the bridge. From this position I saw

a lot more action on the island. The fighting was in it's

first week still. We hadn't gained much ground yet, but we

had a lot of casualties. We started taking them aboard the

Jackson. Anyone not on watch helped out in any way they

could. We ended up with over 350 wounded, some died on

board. They were wrapped up for burial at sea and stored in

cold (refrigerated) rooms until the burial could be done.

The mess hall was used as a sick bay overflow. One marine

was laid on a table in the mess hall and was bleeding

profusely from shrapnel wounds in his back and sides. The

blood ran out as fast as the plasma was put in him. It ran

down the mess hall deck and out the scuppers amidships over

the side into the ocean. I hung a sheet around him to sort

of cover him from the others. He died that night and was put

in a cold room. I helped with feeding and anything else I

could with those who were wounded. There were a lot of foot,

ankle and leg wounds placed in this area. The doctors were

busy amputating in sick bay. Sometimes in the evening hours

they would come down to the mess deck to redress the wounds

which were now pretty bad, lots of sulfa all over them.

There was also lots of face and head damage. The doctors

looked at each other and shook their heads. My watch on the

gun deck went on, four hours on and eight hours off. They

were busy hours and went fast. I had on sound powered phones

and could hear about anything that was happening. I would

relay it to anyone nearby so we could watch it. I saw the

first B-29 land on Iwo, as soon as the strip was taken and

repaired. Those 500 pounds mortars make huge craters in the

ground.

We had one officer aboard who

was about the meanest person in the Pacific. You couldn't

please him no matter no matter how hard you tried or how

right you were. He would make you tear down a gun and put in

back together ... not too difficult ... except he would have

you do it in the dark. One seaman had a small phonograph and

I think only one record, "What a difference a day makes" by

Dinah Washington. He would take this up into the crows nest

and play it into the sound powered phones and we could hear

it. This officer knew it was being done but never found out

from where. He got up on the gun deck but might have been

afraid to climb any higher to seek it out. I was on watch on

the gun deck one night, crouched down with my back against

the stack. I dozed off and a little later I was awakened by

this officer by him putting a blanket over my shoulders. He

sat nearby on a beach chair. I never got to know him. I had

to go back to small boats to continue doing errands etc.

Soon we were filled with casualties, the last loaded from an

LCI which was tied up along our starboard side. This is

where the fenders come in as they separate two vessels from

each other as the swells move both around up and down. We

were called in the following day and the boat was hoisted

and staed up and once more my job was the watch on the gun

deck. The rest of the boats were being hoisted aboard, the

davits full with a boat to the rail. The big booms were

lifting the last few boats onto the ship. The starboard boom

was outboard with a boat that had a canopy on it. It was

about 60 feet above the water when a plate which was welded

to the bulkhead just a few feet below where I was standing,

taking in all the activity, came "unwelded" and shot across

the tops of the stacked boats already on deck. I saw this

plate which was about 3 feet square, go over a man's upper

legs. The load of the boat caused it to go very fast until

it reached the spot where the cable entered another pulley.

The boat being hoisted aboard fell back down until it hit

the rail on the starboard quarter. The engine was the

heaviest part of the boat and as it hit the rail it broke in

two and the whole thing fell down into the sea. One deck

hand jumped and was rescued. The two men in the canopy were

killed and were picked up the next day by a destroyer. One

of the men was the one that had pulled the BAR man to safety

from out of the sea a couple of days before. The ship moved

out and headed south to Saipan, slowed to bury seven bodies

over the side, "deep sixed" them as sailors would say. This

is something to remember. The bodies float in the wake for a

few miles then sink below the surface. I don't know if these

were weighted down or not. I do know they are gone ... that

they never wrote home again.

We unloaded several hundred

casualties which took a few days. I don't know how long we

stayed at Saipan. We moved on south toward Guam and in a day

or more the Fireman First Class were called to the

Engineering Officers quarters, lined up and notified that no

more firemen could advance in rank because the men above

(Third Class Petty Officers) could not advance either. Two

of us would have to leave the ship. There was no sure

destination, maybe another ship nearby, maybe a shore job.

Also a trip stateside may be in order. No one seemed to

know. To decide who would go would be the navy way cutting

cards. The deck of cards was passed down the line and we

each took a card. I had a ten of diamonds and assumed I had

no chance at all. One guy had an ace and out of fourteen men

no one had any thing above my ten spot. The other guy was

Paul Robbins, from Detroit. We got our gear together, signed

a lot of papers to prove we did not owe the ship anything. I

had only a few goodbyes to say. The next morning we got off

while moving along at ten knots. The boat took us to shore,

right up the ramp that the Pan American flying boats used in

peacetime. We were assigned a tent with a lot of mosquito

netting over the cots. Paul and I were the only ones in the

tent. We mustered in the mornings, ate our meals, just sorta

goofed off, trying to get some information about where we

were headed. We found out that we were going stateside but

nothing else. The days went by and more guys were mustering

in each morning, now about twenty plus a first class

machinist mate who was in charge. The group was called a

draft. We were told to stay together and soon we would be on

our way. About three weeks on Guam and then we were boated

out to a big old Victory ship. Talk about a "slow boat to

China". They creek and groan and break in two on occasion.

Anyhow, this was our ride to the States. We boarded via a

cargo net over the side. Our gear was hoisted on deck with

the usual hooks and cables. As I was pulling mine out from

the pile I plopped it down on deck and as it was very tight,

with mattess and all, it bounced back up and pushed my right

thumb about halfway to my elbow. Hurt? You bet! This was a

good start. My rack was the top one in the side of a hold.

We were given a box of cereal and some coffee. That was

breakfast. At noon we had a bowl of soup similiar to Mrs.

Grasses, mostly water. We had a glass of Kool Ade type

drink.

We could hardly wait for

supper ... except there wasn't any supper! Luckily there was

some candy available. One night I was really hungry for some

food of some sort so I decided to go up in the crews

quarters to talk to someone about how I could get some. I

was told that if I would volunteer for a watch I could eat

with them, so, of course, I did. On the way back to my rack

I was in this long dark passageway and feeling my way along

when I came to an opening. The door was not locked. I

reached inside and felt some boxes. I had no idea what I was

feeling. Maybe it was soap and, if so, maybe I could trade

it for some food! I took a few boxes placing them under my

shirt and headed for my rack. The red lights in the berthing

compartment gave enough light to see what was on the boxes.

There was a bunch of numbers and the word "baked" which

caught my attention. I tore open one of the boxes and

discovered cookies ... like Oreos we had later after the

war. I made a few friends that night. I began feeling sick,

weak and sweaty most of the time and found out later that I

had malaria which I had been exposed to on Guam. We had

taken pills to keep from getting it but they obviously

didn't work for me. Maybe it was one big mosquito! I have

some of it to this day as it comes and goes. I stood the

watch ... 4 hours on and 8 hours off ... and got to eat some

good food for a change. This trip back stateside took 3

weeks. I began to feel better each day and passing under the

Golden Gate bridge again made me a lot healthier. I was put

on Yerba Buena, one of the Treasure Islands in San Francisco

bay. Once more I tried to get some information about my

future in the Navy and this time I was successful. I found a

yeoman who looked up my records and he said I had 18 days

delay enroute to San Diego Naval Repair Base so I had a few

days available to go home to my wife and daughter in

Indiana. This being in the 1940s meant taking a train, about

4-5 days each way. The freight trains had the right of way

so the passenger trains had to pull over to the sidings to

let them pass. I headed for Chicago on a normal overloaded

train with old straight seats. There was no possible way to

relax or lie down except on the floor, but it was so full of

luggage and sea bags. In those days we had to lug our

mattresses around along with our sea bags and ditty bags so

it was a very large amount to handle. I arrived in Chicago

and found a train to Waterloo, In. which is about 5 miles

north of Auburn ... my destination. I got a ride in a car to

Auburn with some people who were going to Fort Wayne.

They dropped me off about 3

blocks from my house. As I walked down the street towards

home I felt like I was walking in the air. I saw Deann, our

daughter, with a friend a couple of doors from our house.

They were out in the yard near some flowers. I walked over

to her but she didn't know who I was for sure until I

accepted some flowers from her. We walked home together and

knocked on the door. The other love of my life ... my wife,

Bonnie, was bathing so she answered the door wearing a

towel. My navy gear on the train had been put in the baggage

car. I was concerned that I would never see it again, but it

was delivered to my house a couple of days later. I spent

about six days home ... not long enough ... but I had to get

back to the Navy. I left for San Diego with my freshly

laundered clothes. The train trip back was a little better

than the one to Indiana. People were so nice ... I couldn't

buy anything ... even pillows or soft drinks. I arrived at

the Repair Base but was 4 hours late so I was assigned to

some Marine people to go to the brig where the first thing

that happens is you get the boot camp type haircut and are

put to work on cleanup duty for the whole base. I walked

across the huge drill field (while the Marines drove a jeep)

to a barracks type building which was all new. The Marines

took me into an old Chief Petty Officer who was behind some

wire mesh. The Marines had handed him some papers on me and

my records. He told the Marines that he would take care of

me and they left. The Chief then threw the papers the

Marines had typed up into the wastebasket and asked me how I

would like to go on liberty. I was put in one of the new

barracks nearby where there were a few other guys. They all

spoke to me but that's all. I found an empty bunk and

started putting my gear away. Another guy came in and he was

next to me so we talked a little. He was also just in from

the Pacific theater so we had things in common to talk

about. He told me that they treated us very good because

we'd seen some action and we were being rehabilitated. He

was so right. I was assigned to duty in a machine shop and a

balance shop where we balanced everything from small motor

armatures to huge ship screws (propellers). It was a joy to

work with this group. We could sleep in if we wanted and a

"boot" would get us up in time to get to work. The food was

the best ... two or three kinds of soup each meal, seafood

once a day ... and all very tasty.

I went to class on alternate

nights. This would last for a few weeks. I had liberty on

port or starboard nights (every other night) but I usually

didn't go out. I thought about Bonnie and Deann and how nice

it would be to have them there with me. I called Bonnie at

work and suggested my idea. She quit her job and sold our

Ford the next day to get the money needed to make the trip.

That night they were on a train for California. We lived in

several small apartments, always moving closer to the base.

We went to a lot of stage shows, big bands and good movies.

We went to the zoo a few times and had fun while we could. I

did a job on a huge troop ship which was loaded and in a

huge drydock. Three of the four blades of the screw were

damaged with tips either missing or bent terribly. It must

have hit something huge to do that much damage. The shaft

had to be rotated by hand from inside the engine room to

bring the blades up to a position so we could grind and fill

in the tips. We did real good and got them repaired in less

than a day. The drydock was reflooded and the ship was on

her way ... with no abnormal vibrations or shakes ... so we

must have accomplished our job successfully. This was the

most work I had done since I was at the base. All of it was

interesting and almost fun for a change. Earlier I was

notified that I was assigned to a new ship, the USS Avery

Island (AG-76), which was a repair type ship of the Basilan

class. She was soon to be on her way to some islands near

southern Japan to erect towers for radar and radio

antennaes. Bonnie and Deann returned to Indiana soon after I

shipped out. The group I was in was mostly personnel to

stand watches as needed, but none of this came to be as the

war in the Pacific ended when the Japanese surrenderd. All

plans were changed and we were once again broken up. I was

assigned to a Destroyer Tender, the USS Piedmont (AD-17).

She was a large ship designed and equipped to repair and

service several destroyers at once. She had huge shops

aboard to accomplish about anything needed as well as food

service and medical and dental care for not only her own

crew but the crews of destroyers tied up alongside. I went

into Tokyo Bay area with the surrender fleet aboard the

Piedmont.

We were tied up in a huge

shipyard in Sagami Wan, the entrance to Tokyo Bay. This was

another time in my life in the Navy where I was very pleased

with everything that happened. The crew aboard the Piedmont

... which was now a skeleton crew ... was the best. I asked

for an assignment in refrigeration and was approved for

this. I met all the people in charge. We had our own little

galley. The watches were simple ... just keep the food and

anything that is perishable cold. I had several months of

this duty. My "points" were building up and soon I could be

homeward bound.

My time on the Piedmont

seemed to drag by. I was so excited about the end coming up

soon. Finally one night I was called up to officers country.

I was told that this is it .. to get all my releases signed

... so that I didn't owe the Navy anything and would be

ready the following morning. Of course, I didn't do any

sleeping that night. I was ready and got out onto the pier.

I walked along toward the stern of the Piedmont where I

boarded a landing craft and had a tour of the bay where I

saw lots of submarines, sunken ships, one large battleship

lying on the bottom of the bay with her top deck just above

the waterline. I had been around the area where the Piedmont

was tied up. I had seen a lot of tanks and sat in a few of

them. I had gone into a few large caves in the mountainside

alongside the pier. The Japanese had used them as machine

shops and had lots of tools and other stuff stored in them.

I had found a few souvenirs in the way of tools. I was taken

to a small ship, the smallest I was ever on. I found a rack

and got acquainted with some men already set to go. We were

a happy bunch ... passengers once more. After a couple of

days of looking the ship over we were told that she was

going stateside to be decommissioned. I never found out what

she was doing in the Pacific ... probably some launch for

some admiral or big wig of some sort. We took off like a

speed boat ... probably 20 knots or more ... headed for the

good ol' USA. This lasted for only 3 days as the electric

motor driven ship lost all power ... something wrong with

the generating system. We drifted into the Japanese current

with no way to move ahead into the swells. Our sea legs were

really tested out. Finally an auxiallary generator was

started and we radioed Pearl Harbor to send two sea going

tug boats out to tow us in. The sea was over the deck most

of the time. We wallowed in the swells like a life boat.

Some people finally got some power to the DC motors and this

was enough to make a little headway ... about 12 knots. The

tugs were sent back and we proceeded north and east ...

getting help from the current. We fired all the guns on

board using up all the ammunition and tossed a lot of the

guns over the side ... no bodies this time. Some of the men

had never been around guns like this. They held their hands

to their ears and hit the deck pronto. We made it to the

States in almost 3 weeks. It was a very slow voyage. We

followed the coast down to San Diego and pulled into a dock.

A draft of men was made up and we went ashore on a wharf

where a Red Cross stand had donuts and coffee for a quarter.

Down the line the Salvation Army had the same for free.

I don't recall exactly what

happened that night as to where I stayed although I know it

was on the base. I went to downtown San Diego and had some

fresh salad and milk. A 'draft' was made up of a group of

men, all going to Chicago. We were all warned not to get

lost or separated or our discharge date could be delayed a

month or so. So many guys had to go out and see how drunk

they could get. I'll never understand that way of thinking.

A lot of questions were asked during the discharge

procedure, mostly of our attitudes, our overall treatment

and care, and a little about what we would be doing after we

got home ... like work and where we would be living a year

from now. Finally the big moment arrived when I went out the

gate to get a train to Chicago and then another train, the B

& O railroad, to Garrett. I suppose it was 6 hours or so

from Chicago to Garrett when I finally arrived at the

station where Bonnie, Deann, mom, dad, and my sister came to

meet me. We went to my parents' home and ate. Later my

sister loaned us her car and Bonnie and I went to Auburn.

This was a lot of excitement for one day! My former

employer, General Electric, was on strike at that time so

going back to work for them was not an option. I wanted to

continue my training in toolmaking so I went to work at a

small shop in Auburn. This was the very next day after

arriving home which was probably too soon, but our financial

picture didn't look too good and the money was needed. All

through the years I worked at several places leaning a lot

about my work. I made tool and die, mold making and

prototype modelmaking my life's 'career'. It has been a good

career and has certainly been something I have enjoyed

doing. This has nothing to do with my navy career, but I

wanted to share some of the transition to the new life back

as a civilian. I retired at age 62 from the company where I

was last employed. However, I continued to work at home in

self employment for another 20 years doing a variety of

things including small engine repair, saw chain sharpening,

harmonica repair, general repair, and machining. I had only

a few machines out in our garage but they were enough to do

a lot of work ... the same sort of work I had done all my

life. Some of that work included making guns for radio

controlled model ships of war used by hobbyists for mock

battles they have on ponds and certain other waters. These

mock battles are among those of WW2 ... some of which I

witnessed in Leyte Gulf in the Philippines as ships engaged

in the real thing. If you do a search on the internet for

"bill newbauer" (using quotations) in a good search engine

such as Google you will find among the results my name

associated with these guns. They are also known as "Indiana

guns". I finally had to sell my machinery and retire from my

life's work. Bonnie was having some physical problems due

mostly to Diabetis which required me to devote myself to her

as full time care giver. And her condition and needs

required us to make a hard decision to sell our home and

move to the Fort Wayne area to be closer to Deann and her

family so they could help us out. Sadly, Bonnie was only

able to live in our new home for about a week before she

took a turn for the worse and had to be hospitalized. From

there she went into a nursing home for less than 3 months

before I lost her in death. I miss her so very much and it

is hard to go on without her. But I am going on as I must.

Even though my navy career ended some 66 years ago in some

ways it has never ended as I have recurring dreams at least

once a week where I am back in the navy. That's about it.

Some people are interested in this sort of story while

others could care less to hear about it. If you have read

this far you obviously are one of the first group. Thank you

for your interest.

Bill

Newbauer

F1C

USNR

A very special

THANK YOU is extended to BOTH Bill and Steve Newbauer for

their kind and generous permission to use the materials

contained on this web page. Stories such as this story go a

long way in preserving yet another piece of the overall

picture that was World War II.

26

June 2011

It

is with extreme saddness that we at World War II Stories --

In Their Own Words pass on the following information

received from Bill's son, Steve...

"...I am writing to inform you that my dad,

William (Bill) Newbauer passed away into eternity last

month..."

Some web sites

that are about the U.S.S. President Jackson

(APA-18) and related material:

DANFS

USS President Jackson (QP-37-APA18)

Ships

of the U.S. Navy, 1940-1945, USS (APA-18) President

Jackson

Online

Library of U.S. Navy Ships - President Jackson

(AP-37-APA18)

Online

Library (additional images) USS President Jackson

(QP-37-APA18)

Attack

Transport -- APA-18 President Jackson

AP-37

USS President Jackson

USS

President Hayes Association

Associations:

USS President Jackson (QP-37-APA18)

Reunions

and Contact List (USS President Jackson)

WWII

Hero Interviews

Attack

Transport -- APA-18 President Jackson

Original Story

submitted 30 April 2002.

Story updated on

26 June 2011