FURY,

FUMAROLES AND BRIMSTONE

The Japanese

Named It Sulfur Island.

The U. S. Marines

Called It (Censored)

----- by TONY

WELCH

For seven

months -- May through November, 1945 -- George E. Pickett

and three fellow sailors held sway over what would soon

become the world's most iconic and instantly recognizable

piece of real estate.

None of them

held a trust deed to the property, and yet this foursome

lorded over their patch of ground with all the authority of

a cop on the beat. Trespassers and interlopers were warned

away by a sign reading: "DANGER -- 5,000 VOLTS! KEEP

OUT.

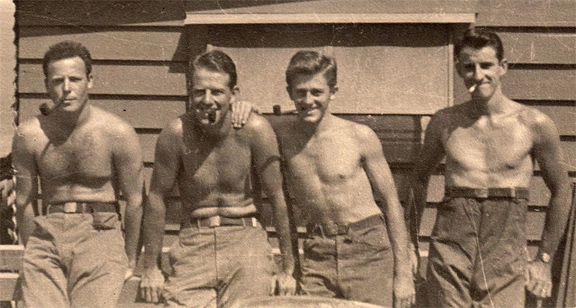

HIGH AND DRY:

Mountain-top sailors (from left): Robert Robertson, Charles

Shimmin, George Pickett and Robert Ray. Together, they set

up and maintained an elevated radar tower atop Mt. Suribachi

within 25 yards of the much-celebrated flag-raising

site

"Each time I

stepped out the front door of our Quonset hut, there was

this sprawling panorama five hundred feet below," Pickett

recalls. Not more than 35 feet away, an American flag danced

atop a new flagpole. "On a good day I could see clear to the

north end of the island, five miles away."

The island

referred to is Iwo Jima, and the viewpoint facing Pickett's

mountain home is exactly where the U.S. Marines planted the

Stars and Stripes atop Mount Suribachi. George first came

ashore on Iwo thirty-five days after the flag raising. He

would spend the next seven months treading the consecrated

ground upon which the eyes of millions became fixated --

thanks to a single photographic image.

THEN AND NOW:

A double dose of U.S. naval gunfire explodes on the crown of

Mr. Suribachi a day before the invasion. The salvo just to

the right is very close to the future flag-raising site. The

crest of Suribachi as it appears today; the speck of white

is the memorial dedicated to all who lost their lives on

Iwo.

Pickett's

assignment -- classified Top Secret -- was to help make Iwo

and its surrounding waters a more secure place by

introducing radar to the island, which technical advancement

had proven invaluable at sea during surface engagements with

the enemy. Initially trained as a radio technician, George

went through a further 18 months of radar instruction before

being assigned to a sector known as GROPAC 11 -- Group

Pacific Eleven. GROPAC's hush-hush mission was to install

elevated radar-ranging equipment on certain specified

islands throughout the Pacific. Pickett and a boatload of

technicians departed San Francisco on February 1, l945

aboard a Dutch vessel and crew leased to the U.S. Army. "We

stopped at five islands in all, over a period of sixty

days," Pickett notes. "While underway at night we had to

take turns manning the crow's nest, because the ship had no

radar. Would you believe we got paid extra for that? --

fifty cents an hour. When we arrived at Iwo on April first,

a large group of departing marines came aboard and we went

ashore in their LSTs. I left the ship with sixty bucks, cash

in hand. Never could figure that one out."

SCENE FROM

ALOFT: An Avenger torpedo bomber pilot, flying from

an offshore aircraft carrier, takes in an eagle eye view of

Mt. Suribachi three weeks after D-day.

On his first

morning ashore, George carefully picked his way across a

mutilated landscape. Knowing virtually nothing of the

unrestrained violence that preceded his arrival, Pickett was

suddenly brought up short by an open trench layered with

Japanese soldiers. An obviously hardened Seabee bulldozer

operator repeatedly ran his tracked vehicle back and forth,

gradually filling the gravesite. One of many mass burials,

as it turned out. Pickett's second rude awakening came when

he learned that beneath the island's surface of volcanic

pumice were thousands more entombed Japanese, scattered

along eleven miles of tunnels and in innumerable caves. An

alarming number of them, as the Marine invaders were quick

to discover, remained very much alive and aggressively

combative.

Less than a

week prior to Pickett's arrival, a force of 350 determined

survivors left their underground labyrinth and in the

pre-dawn hours of March 27 infiltrated the Marine lines

undetected. Pausing briefly to regroup, they then assaulted

the sleeping quarters of the 7th and 21st Fighter Groups.

Amidst total confusion, the groggy Mustang pilots suddenly

found themselves overrun and outnumbered. Within the

spread-out tenting area, chaos reigned. In one encounter,

some cooks armed only with long-handled soup ladles and

other kitchen utensils drove six Japanese out of the mess

tent -- and lived to tell about it. From outside the

perimeter, U.S. ground crews and other support personnel

quickly joined the fray. The frenzied Japanese ransacked the

area, tossing grenades inside tents and then gunning down or

bayoneting any survivors attempting to flee. When the

skirmish finally ended at mid-morning, 330 Japanese lay

dead; those not killed committed suicide. Forty-four U.S.

pilots and support personnel died, with another 100 wounded.

The encounter marks the only known WW11 engagement between

aviators and infantry. "Our own tents near the airfield were

only a few hundred yards away from where the attack took

place," Pickett remembers. "That's when we starting posting

armed sentries at night."

In consequence

of the mounting death toll on both sides, hundreds and then

thousands of bloating bodies became feeding and breeding

grounds for millions of flies. Marine and Seabee sanitation

teams, often under fire themselves, quickly fell behind in

their recovery efforts. In a moment of inspiration, a pair

of C-47 cargo planes was outfitted with improvised spraying

equipment. The aircraft made repeated low-level passes over

Iwo's terrain, leaving in their wake misty clouds of DDT.

The disease-carrying fly population -- just one more threat

to human health -- plunged dramatically. The bushido-driven

Japanese proved far more resilient.

GROPAC's first

project, at the far north end of the island, was to install

seventeen radio transmitters for the joint Army/Navy

Communications Center. Each transmitter was equal in size to

a refrigerator; the condensers stored within were wired and

bundled, then each unit connected in sequence. "It took

close to a month to complete," George notes. "After we

finished, the Navy officer in charge went out to a ship and

brought back a pile of steaks that we cooked up on a grill

-- his way of saying thanks. And I got advanced to petty

officer second class."

|

|

|

CHEESE

PLEASE: A.P. photographer Joe Rosenthal records a picture of

the Suribachi flag raisers. But it's not this posed image

that would capture America's heart and soul and later earn

him the Pulitzer Prize. The Associated Press, in an

unprecedented gesture, donated all proceeds from the sale of

Rosenthal's famous grab-and-shoot photo to the Navy Relief

Society -- a total of $12 million over ten years. At right,

Easy Company marines climb Suribachi's north flank with the

first of two flags flown that day.

Next stop:

Suribachi. Within the walls of its volcanic cone -- as well

as along the steep slopes rising 550 feet above the island

floor -- dozens of cave entries were discovered shortly

after the flag raising. Flame throwers and dynamite satchel

charges were lugged up the mountainside. In one cave alone,

by actual count, 142 charred bodies testified to the

effectiveness of flammable napalm. How many cave dwellers

remained was anyone's guess, connected as some caves were to

tunnels leading downhill to the island itself. But for the

moment all was peaceful on the mountaintop -- and there was

every hope that it would remain so.

"A

construction battalion roughed out a two-lane road up the

mountain, and we used our assigned weapons carrier to haul

all our gear and unassembled parts," Pickett explains. "The

winding mile-long road ended about fifty feet below the

highest point of the volcano's rim, on a leveled plateau." A

just-erected but empty Quonset hut -- home sweet home --

greeted the quartet.

Adds George:

"The Seabees also built a four-hole outhouse nearby, so that

each one of us had his own throne." Pickett seriously doubts

if any prowling Japanese ever used it. "One of the first

things we did was build a shower stall, using a 150-gallon

external fuel tank from a P-51 Mustang fighter plane. Shaped

like a teardrop. We installed the tank on top of the shed

that housed the motors that ran the electric generators.

Talk about king of the hill!"

Pickett on

more than one occasion expressed delight at finding himself

in a war in which he was totally ignored by the enemy. "I

never once got shot at!" he'd exclaim, feigning

disappointment at being short-changed -- but in reality

profoundly grateful, as evidenced by a toothy grin.

Nearby, a

thirty-foot steel tower loomed above the compound. The plan

was to attach the radar oscillator at the top, then follow

through with all the necessary connections to the electronic

apparatus packed away and waiting assembly.

With a

Raytheon company technician standing by, the four-man team

finished the complex task in a week. To Pickett's surprise

and delight, the radar apparatus immediately came to life

and did what it was intended to do: detect any approaching

or passing surface vessel within 35,000 yards. The great

majority of Allied shipping in that theater of war was

equipped with a sensor that automatically returned a coded

signal to the GROPAC station atop Shuribachi. Any vessel

under radar scrutiny that failed to respond was presumed to

be unfriendly. "The Army Air Corps on the island operated

similar radar towers to detect approaching enemy aircraft,"

George explains. "I remember seeing B-29s taking off and

landing on our radar screen as the revolving oscillator

picked them up. It only broke down once during the seven

months of continuous operation." A nearby duo of gasoline

generators supplied 5,000 volts of electricity to the

system.

Pickett

graduated high school in Wheeler, Oregon at age 16, then

went to work for a journeyman carpenter in need of an

apprentice. By the time he enlisted in the Navy on his

twenty-first birthday -- and newly married to boot -- George

was thoroughly familiar with residential construction,

having helped erect five dwellings. He also delved into wood

carving and furniture making, a vocation he was to pursue in

later life.

Standing alone

in the empty 20x48-foot quonset, George quickly sketched out

a workable interior design. "I set aside one-quarter of the

space for us four guys. Then half of the hut to hold all the

radar gear. The last section went to house Joe Hayes, the

lieutenant jay-gee in charge. Hayes was an OK fellow, a

school teacher from the Midwest somewhere. He was seldom

aroundÉleft us pretty much alone. And would you

believe -- he didn't drink! Sweet man -- he sold us his

weekly booze allotment for the same price he paid for it."

Hard liquor, especially well-aged bourbon, was the currency

of choice on Iwo. Nothing else of value came close,

excepting genuine Japanese flags, sidearms and samurai

swords for which the liquor was eagerly traded.

With lumber

and tools supplied by the Seabees, Pickett partitioned off

the quonset and then proceeded to furnish the interior. He

designed and constructed four spacious bunk beds (no army

cots for these swabbies). Then a table and chairs, plus a

large dresser with four drawers, one for each occupant.

Further personal touches followed, and living began to

resemble more of a peacetime setting than a war

zone.

HANDY ANDY:

George Pickett's woodworking skills are evidenced by a

homemade lamp and bedroom dresser, plus an array of bunk

beds to brighten the Quonset hut. The skull and warning sign

(center) serve as grim reminders of the war being waged --

literally underfoot. The samurai sword was 'rescued' from a

subterranean Japanese bunker.

Making the

best of it atop Mount Suribachi wasn't all domestic

tranquility, to be sure. During installation of the radar

tower, a human skull was unearthed -- undoubtedly Japanese.

"We decided to hang it just below the posted danger sign on

the tower, to give the warning further emphasis. Somebody

came up with the bright idea to insert two lights within the

empty eye sockets. The lights served to illuminated the

skull and warning sign at night." The adornment must have

done its job, George reflects, because to his knowledge no

surviving Japanese lurking in caves within the mountain ever

came snooping around the premises. For a final touch, a pair

of eye glasses was added -- after all, weren't all Japanese

born near-sighted? Newspaper and magazine cartoonists early

in the war liked to portray them wearing inch-thick

spectacles. "That's what everybody was led to believe back

then," Pickett notes. "That is, until the shooting started."

|

|

|

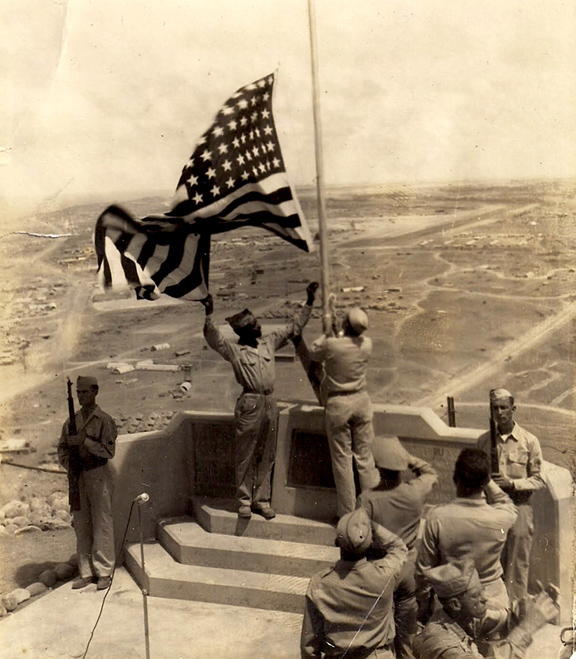

ABOVE AND

BEYOND: Custom-designed and built by the 31st Naval

Construction Battalion (Seabees), the Suribachi memorial was

dedicated October 2, 1945 by a U.S. Army occupational

detachment. The flag was later replaced by a bas-relief

bronze tablet, seen here.

A group of ten

Navy radar operators took turns commuting to the

mountaintop. Their task: monitoring the radar scopes 24/7,

while Pickett's on-site crew of four maintained the power

plant and electronic equipment. One of the radar operators,

a second-class petty officer named Jack Gary, decided to

fill his off-duty time with a new hobby. Armed with a

portable tank of oxygen and connective breathing tube (plus

a lantern and .45-calibre sidearm), Gary began exploring

unsealed caves and tunnels he thought reasonably safe to

enter. Not for nothing had the Japanese named this place Iwo

(Sulfur) Jima (Island). Ascending sulfur fumes from hundreds

of fumaroles scattered across the devastated landscape

provided a constant reminder that 'Iwo was hell -- without

the fire,' as one Marine aptly put it. The highest

underground temperature ever recorded on Iwo was 156F; even

more troublesome, nowhere on the island was there a natural

source of drinking water.

IN

REMEMBERANCE: Returning Iwo veterans often leave their dog

tags as a symbolic tribute

to fallen comrades.This 2010 anniversary tour consisted of

26 vets ranging in age from 83 to 97

(photo courtesy Vernon Martin, "Sgt., USMC)

"I went along

with Jack a couple times," says Pickett. "We navigated one

of the tunnels and it finally opened up into a rather large

excavation. I think it might have been a hospital, or

emergency room." Slumped along a bench against one wall, a

dozen Japanese soldiers in the first stages of mummification

testified to the utter hopelessness and despair of their

troglodyte existence. "One of them had his arms folded

around a samurai sword," Pickett continues. "Jack scooped

that up in a hurry, and then he proceeded to look for wrist

watches. Finally, he got out a pair of pliers and started

yanking all the gold teeth he could find. He later made

rings out of monel, a nickel and copper alloy, with some of

the better gold teeth mounted in the center. I don't

knowÉthat's just the feeling some guys

hadÉalmost an automatic reflex. No more regard than

if the Japs were animals."

Then came a

day in late November; time to pack it up and pack it in.

George remembers: "We carefully dismantled all the

classified radar equipment and boxed it, well padded and

secure. And that included the skull from the tower, in its

own special container with the eyeglasses and all. Lord

knows, thoughÉour shipping containers probably ended

up at the bottom of the ocean -- just another pile of

post-war surplus." Pickett gave the room a final once-over,

then walked through the open doorway for the last time and

across the hallowed ground, clutching his seabag.

Part fantasy,

part Dante's Inferno, part netherworld -- the imagery of Iwo

Jima will likely remain in the American consciousness for a

very long time. As in: "My great-great-great-great

grandfather fought on Iwo Jima." George Pickett well knows

he got but a whiff of what transpired there, and is ever

grateful for being spared the savagery* that engulfed so

many others of his generation.

George

Pickett at age 22, and now a spunky 88. George and his wife

Thelma have been wed 68 years, and reside in a suburb of

Portland, Oregon. Coincidentally -- or perhaps

intentionally? -- sons Mike and Harold both served in

Vietnam as electronic technicians. One Navy, one

Marines.

*For each of

Iwo's eight square miles, 3,255 American servicemen were

killed or wounded. Add to this figure 21,060 Japanese

casualties, and the total exceeds 46,000

dead/wounded/missing in action over a 45-day period.

Recovering A Nation's War

Dead...

|

|

"Japan's prime minister

and other officials gather to pray at a newly

discovered Iwo Jima mass gravesite on December 14,

2010. More than 12,000 fallen Japanese

soldiers have yet to be recovered from the

island."

|

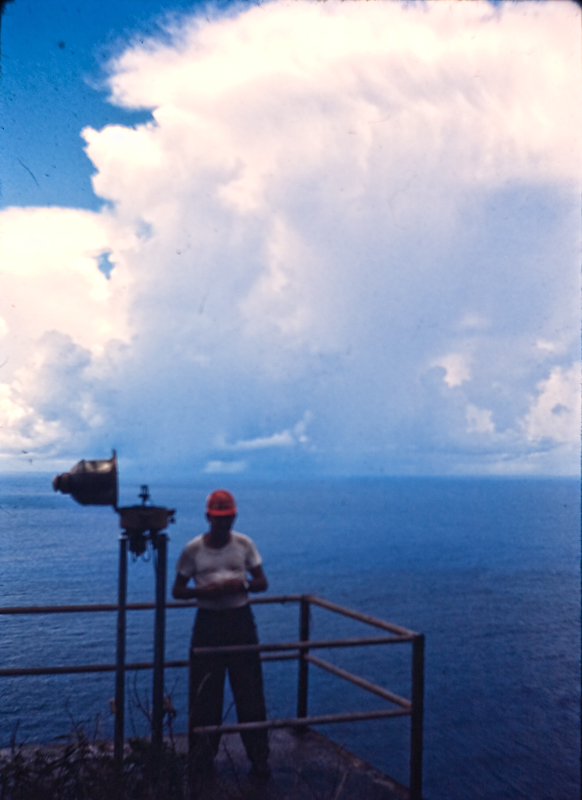

E P

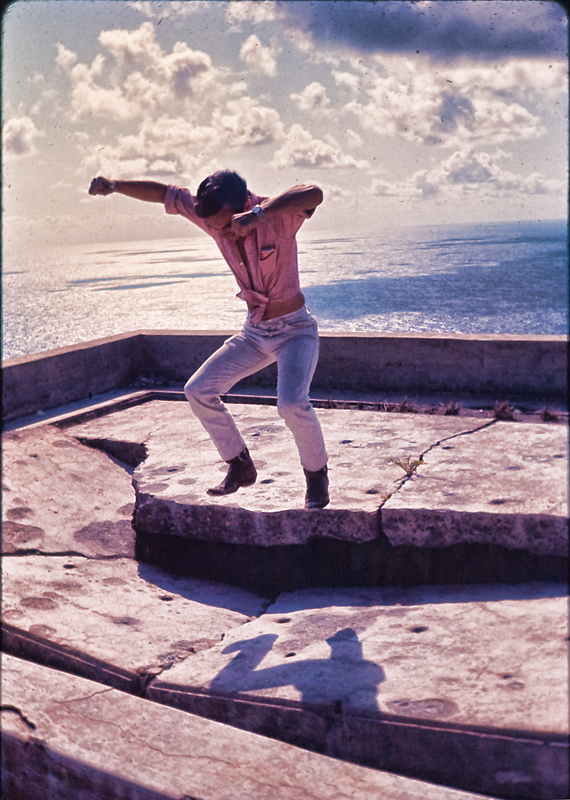

I L O G U E: YOUR WEBMASTER -- THAT'S ME, JOE RICHARD

-- VISITS SURIBACHI ONE LAST TIME, WHERE HE SAT OUT A

PASSING THUNDERSTORM (see below). GEORGE PICKETT DID

THE SAME 21 YEARS EARLIER -- BUT HIS STORM TURNED INTO A

CLASS 3 TYPHOON THAT TOPPLED HIS QUONSET

HUT.

Large version of one of the images in Mr.

Pickett's story: In looking at the above image, you will

see the white arrow that points to the spot where the flag

was raised during the early days of the battle for the

island. If you look to the left of the arrow and almost

halfway and slightly lower in this photo, you will see a

small concrete structure. That is the observation post where

I waited out the storm. Moving further to your left, you

will see a white area with what appears to be a square

concrete structure. One of the images below was taken

there.

Webmaster

note: Back in 1966, a few days before leaving Iwo Jima for

home, I hitched a lift to the summit where a crew was headed

up to change the beacon light on top of Mt.

Suribachi.

While up on

the summit, we could view some thunderstorms that were

building and were headed directly towards the island. It was

quite a sight to see.

The guys

finished up the bulb replacement and were ready to head back

down before the storm arrived. I elected to stay on the

summit and utilize the observation post (located mid center

of image above) and wait out the storm. Over their

objections, I stayed.

The shower

approached and passed directly over the island with the

ragged base BELOW the summit of Suribachi.

Taking refuge

in the observation post, I snapped some shots of the rain

and cloud base as it passed over me.

Some of the

images are shown below.

|

|

|

|

Replacing the bulb atop

the observation post.

T-storms advancing towards island in the

background.

|

|

|

Inside the observation

post as storm passes overhead.

|

|

|

...from inside the

observation post looking towards broken concrete

structure.

|

|

|

The showers passing over

the invasion beaches.

|

|

|

Showers ending above

island.

|

|

|

...concrete structure

shown in original photo above.

|

|

Note:

To view images taken by the web master on World War II

Stories -- In Their Own Words during his year on Iwo Jima,

please click on the following link to my World War II

Stories Photo Album:

WW

II Stories: Iwo Jima Photo Album

1965-1966

Did YOU serve on Iwo Jima?

Did you

know that there is a group of veterans who have gotten

together to form an association of servicemen, no matter

what branch of service, who served at one time or another

starting at the invasion of the island on February 19, 1945

and continuing until the island was eventually returned to

the Japanese in 1968?

Iwo

Veterans Organization

We, at

the Iwo Jima Memoirs web site wish to

offer to Mr. George Pickett our most profound THANK YOU for

his poignant story of his personal experiences -- during his

tour of Iwo Jima and especially for allowing us to share

those memories.

Original story transcribed on 14 September 2011

Did YOU serve on

Iwo Jima?

Do

YOU have a story to tell?

Do YOU

have a picture or pictures

that tells a story?

Contact me, Joe Richard and I can help by

adding YOUR story to my site devoted to veterans who served

on Iwo Jima.

Check out my

other web site on World War II. Click on the Image

Below: